How to use storytelling to teach a language

Using stories to take students from input to spoken and written production.

It’s been amazing to have spent two weeks here at Semiahmoo Secondary School learning about using storytelling to teach a language. Spanish teacher and Head of Department Adriana Ramirez uses comprehensible input methodologies (in the form of stories and novels among other things) to teach Spanish to all her students, many of whom go on to join the International Baccalaureat Diploma programme. I’ve been blown away by how well her students speak and write Spanish.

Adriana uses stories to help students in their journey to acquiring Spanish. Her approach is very much input-driven, drawing on second language acquisition research by the likes of Stephen Krashen and Bill VanPatten. Storytelling is one of many ways of providing comprehensible input to our students. I learned more about storytelling and comprehensible input methodologies at The Agen Workshop, a conference for languages teachers that takes place in southwest France in July.

Using stories is a different way of teaching from the typical methods we tend to use in the UK. In the UK we often use a traditional textbook like Stimmt, Viva or Studio, and in recent years many teachers have adopted Gianfranco Conti’s Extensive Processing Instruction (EPI).

Why stories are so powerful

There are few advantages to using story and narrative in the languages classroom:

1. Students get lots of comprehensible input via stories - much more than a traditional textbook approach. This is really important for language acquisition, and the focus on reading helps students’ general literacy skills.

2. A story gives you something to talk about. We need to communicate to learn, but often in languages classes there isn’t much interesting content to talk about.

3. Stories help us to remember vocabulary by couching it in a particular scenario.

4. Stories open up a whole realm of interesting vocabulary and enable a lot of repetition of language (which is vital if students are to acquire language).

5. Stories are enjoyable and can be very funny indeed. This lowers the affective filter and helps out students to learn.

How to use a story in class

Over the past week I’ve watched Adriana take her beginner’s Spanish class through a sequence of steps that moved from input to written production. (For an example of a story, see the bottom of this post).

1. Tell the story using vocabulary displayed on the board as a scaffold. Adriana went very slowly and used lots of structured questioning and repetition to ensure students understand every detail of the story. All of this was done in Spanish and students can determine some details of the story (e.g. name of character, where they come from etc). Adriana took two lessons to tell the story.

2. Structured writing. At the end of each lesson, Adriana typed up on the screen the story so far, for all students to write down. While she did this, she recapped the story by asking the class lots of questions about the details. By the end, the students will have written the story down in their folder/notebook.

3. Ping-pong reading. Students read the story that they’ve written, taking turns with a partner to read the text in Spanish and translate each sentence into English.

4. Skits. In groups, students write a script based on the story in the first person. They play the various characters and can even invent an imaginary character. They then perform the skits for the class without notes. This ensures students have actually internalised the language and aren’t just reading off notes. Students are encouraged to be spontaenous and to go off script. Adriana didn’t correct any errors in speaking – the focus here is developing fluency and having fun speaking.

5. Homework – students re-read the story at home and draw a comic to illustrate the story. This can also be done as a Powerpoint if students don’t like drawing.

6. Review of story using the comics the students have prepared at home. Adriana retells the story using the comics and class questions.

7. Extended reading. The class get an augmented version of the story. Some details might be changed and extra vocabulary added, but the story is fundmentally the same. Roughly 80% of the language will now be familiar, and 20% new language. Adriana reads the text aloud and the translates the text one sentence at a time. Students note new vocabulary above in the text.

8. Ping-pong reading. Students re-read the story with a partner and translate orally.

9. Comprehension questions. Students write answers in Spanish to L2 questions. Adriana goes over their answers with the class.

10. Retell of story. Students retell the main points of the story, and are encouraged to go further with the details.

11. Test. At the end of the sequence pupils are given a writing test. They’ll be asked to write a their own version of the story (changing some details), add a new character/dialogue and show what they’ve learned from other sources (like the songs they do in lessons). Students are asked to write around 300 words. Adriana’s students managed this very well.

Some reflections

· Much of the class involves oral interaction and input from the teacher. Adriana uses “circling” (structured questioning )to check for understanding and to provide lots of input. The class is trully immersive – I’d say at least 90% of Adriana’s lessons are in Spanish, yet she manages to keep everything comprehensible.

· Free writing is delayed to the very end of the sequence, when students have had lots and lots of input. By this point they are very familiar with the vocabulary and structures used in the story.

· Grammar is naturally embedded in everything Adriana does. She highlights verb endings and tense by pointing to some aids on the wall and using hand gestures. Very occasionally she might do a 30 second grammar explanation when needed, but this is always kept brief and is in context. There is no explcit grammar practice.

· Lesson time is maximised and input in the form of oral speaking or reading is prioritised. There is no “busy work” where students tread water filling out worksheets.

· While the teacher plays a key role in provided a lot of oral input, the lesson is interactive. Students are kept accoutable by constant cold calling. I was amazing at how used they were to this, and the students were very keen to answer questions in Spanish. The atmosphere in the classes was focused, productive and positive.

· Teachers that use this way of teaching don’t tend to teach language in clearly defined units (e.g. My family / My free time). However, all of this vocabluary can be covered within the stories. This is much more natural and enables students to acquire key verbs and vocabulary over time, rather than in arbitrary “topics”.

Where to begin?

If you’re curious about teaching with comprehensible input methodologies, why not check out Adríana’s YouTube channel Teaching Spanish with Stories or Liam Printer’s podcast The Motivated Classroom. You can find Adriana’s curriculum books and novels on her website. You might also be interested in one of the various training conferences in Europe such as The Agen Workshop.

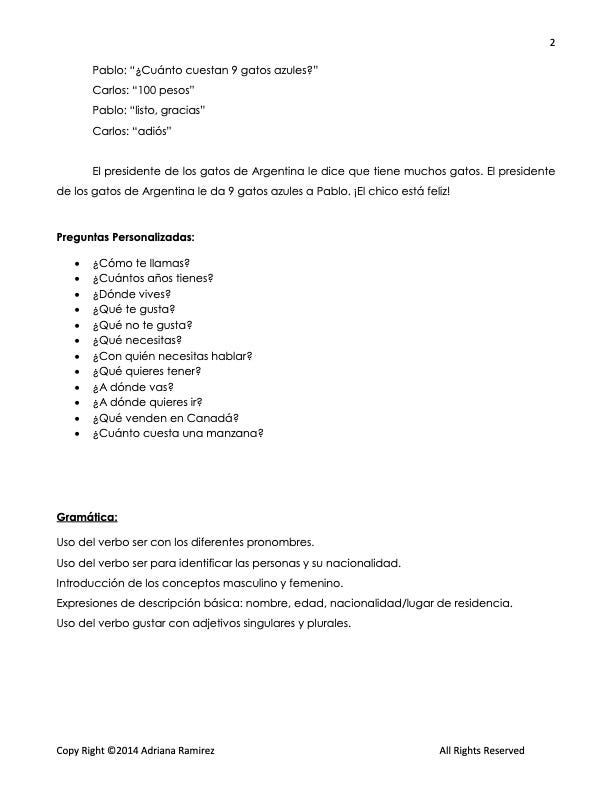

(Below: an example of a story from Adriana Ramírez’s curriculum book “Teaching Spanish with Comprehensible Input Using Storytelling”)