Why extensive reading is beneficial for language learning

Using graded readers to boost the amount of input language learners receive

Why don’t we read more for pleasure when learning a language? I started to think more about reading in the languages classroom after hearing Dr Liam Printer talk about it on his podcast The Motivated Classroom. I was interested to hear Liam talk about how his students start every lesson with five minutes of silent reading using graded readers (novels written with a limited vocabulary appropriate to the level of the student).

A level 2 graded reader by Adriana Ramirez.

As well as reading in class, many schools in Canada and the US promote extensive reading or free voluntary reading. Extensive reading is when students read lots of graded readers outside the classroom, usually at a level that is comprehensible to them (in other words, they’re able to read relatively fluently, and aren’t looking up every second word in a dictionary).

There’s a lot of research that suggests that extensive reading is beneficial for second language acquisition (Mason and Krashen 1997; Nation 2001; Waring 2006). In fact, Paul Nation goes so far as to say it’s the one thing that can have the biggest impact on learners’ progression. Interestingly, extensive reading programmes seem to be uncommon in UK schools and I haven’t come across any schools in Scotland who routinely promote it. (If you’re reading this and you have extensive reading in your school, please be in touch!)

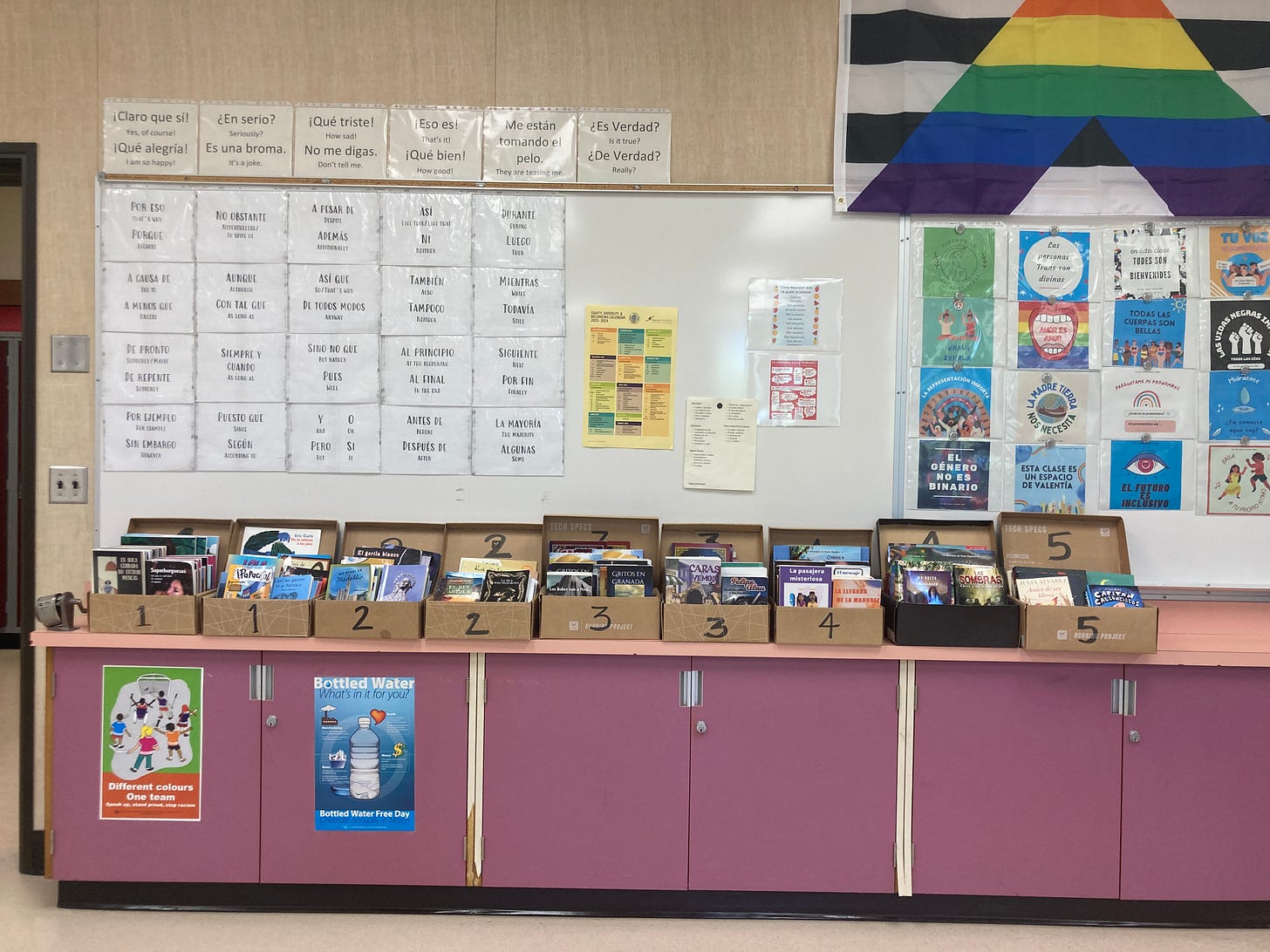

A class library of graded readers in Semiahmoo Secondary School, categorised by the level of difficulty.

So why is extensive reading so beneficial? Rob Waring wrote a really good article on this called Why extensive reading should be an indispensable part of every language program. I’ll mention some of his points, as well as some of my own thoughts:

1. Extensive reading allows students to learn vocabulary in context. We know that it takes quite a while to learn a word fully and that we need to know a word in its many different contexts. Take for example the word chair. I could learn this as a noun, i.e. the thing we sit on when we want to rest. But it could also be the verb, as in to chair a meeting. Learning the word in a vocabulary list might mean I understand one meaning, but it will take many more encounters with the word until I understand its other potential meanings.

2. It allows for extensive repetition. Often we’ll need ten or twenty encounters of a new word until we know its meaning and retain it in our long-term memory. Extensive reading allows for this level of repetition, but a fictional story or narrative means this doesn’t have to be boring.

3. Narrative can be a powerful tool for remembering new words. Since words are learned in the context of a story, associations are made with places, characters and events. Typical textbook texts don’t offer this context.

4. Extensive reading helps consolidate previously learned words. We tend to forget new vocabulary quite quickly, but reading can help us recall previously learned words that we might have forgotten.

5. Extensive reading increases the amount of input students get outside the classroom. This is quite important in a UK context, since most school pupils in UK schools don’t get much contact time in their language per week. I see my beginner classes twice a week and my National 5 exam classes three times a week. Because contact time is scarce, extensive reading is a useful additional tool to have in our box.

6. Free voluntary reading programmes offer our students autonomy, especially if they are allowed to choose the books they want to read themselves. Autonomy is a key factor in intrinsic motivation (for more on Self-Determination Theory, check out Liam Printer’s podcast The Motivated Classroom).

7. Extensive reading allows learners to develop fluency in their reading. Often we concentrate on intensive reading in class, where we read a text slowly and intensively work on the vocabulary, but we forget that reading fluently is an important skill too.

8. Extensive reading aligns language learning with a broader approach to literacy. Often we frame language learning in narrow, utilitarian terms, focusing on the opportunities for employment and travel. While these are valid reasons to learn a language, are we forgetting that language learning is at its core about literacy? The ability to read in another language is a hugely enriching skill to have, even if we never step foot in that country.

At Semiahmoo Secondary School in Vancouver, teachers have a selection of graded readers that students can help themselves to and return once they’ve read them. They self-select a book at a level that is appropriate, and if they don’t like the book, they can return it and select another. It takes some time to build up a class library, but even adding a few books every year can result in a small library that students can access.

Sometimes it can be difficult to find reading material that is at an appropriate level and is truly comprehensible for our students. The CI Bookshop is a great place to find graded readers at all levels, including for beginners.

Coming soon: A conversation with Vicky Schrader about how she uses free voluntary reading with her English as an additional language (EAL) students at Semiahmoo Secondary School.

References

Mason, B., & Krashen, S. (1997) Extensive reading in English as a foreign language. System 25(1), pp91-102

Nation, P (2001). Teaching vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Waring, R (2006). Why extensive reading should be an indispensable part of all language programs. in The Language Teacher 30(7) pp44-47